Growing up in the 1970s near Denver, Colorado, my friends and I roamed fields and ditches of suburban paradise until our parents summoned us home. For some kids, the signal was the clang of a cowbell. Another family rang a triangle-shaped dinner bell on their porch. My mom honked an old-fashioned foghorn that sounded like a distressed goose. We heard these signals and raced home as sunset faded into night.

Wide-open sky was with me always, I felt, like a formless guardian angel.

I was a gender-nonconforming girl, but most of us were. Boys and girls alike wore shaggy hair, bell-bottom jeans, t-shirts, and puka shell necklaces. This was the era of Free To Be You And Me, a 1972 television special and music album about rejecting gender stereotypes.

I was eight years old in 1973. My third-grade teacher wrote a stage play called Suitiful Binderella, retelling Cinderella with boys playing girl roles, and girls playing boys. My friend Derek was cast as Suitiful Binderella. I won the part of Pandsom Hince. The play was a comedic blast of role-reversal fun. I don’t remember anyone being confused or provoked by it.

Which is not to say all was well in our world. Bad things happened. For instance, Marilee Burt, a 15-year-old cheerleader, was abducted and murdered while walking home from our neighborhood school in 1970. The crime remains unsolved. In 1979, Michelle Conley, age 11, was abducted and murdered at the nearby country club where I learned to swim.

Even in our enclave of seeming privilege and protection, children were stolen, used, and killed. We questioned gender norms, yes, but we could not escape our sex. We knew, as girls, when men or older boys showed particular interest in us, it could be very dangerous.

When I was 11 or 12, all-girl sleepovers called slumber parties were the rage. My mom said Derek and Ricky could not come to my slumber party because they were boys. Their moms understood. There were no hard feelings, I was told.

I don’t think Ricky understood, nor did I. Our friendship did not survive. Decades later, I saw Ricky walking in the neighborhood with his wife. He vaguely recognized me, I think, as we said hello and kept walking in opposite directions. I almost wanted to say, “Sorry I couldn’t invite you to my party, Ricky. I, too, was sad.” Would he have known what I was talking about, even?

Of course, a mixed-sex slumber party for pubescent kids would have been stupid, I now understand. Back then, puberty was considered a natural, healthy part of growing up. Girls went through different changes than boys, and it was emotionally fraught for everyone.

The ethos of our era was defiance of masculine and feminine stereotypes, after all, not denial of male and female sex differences.

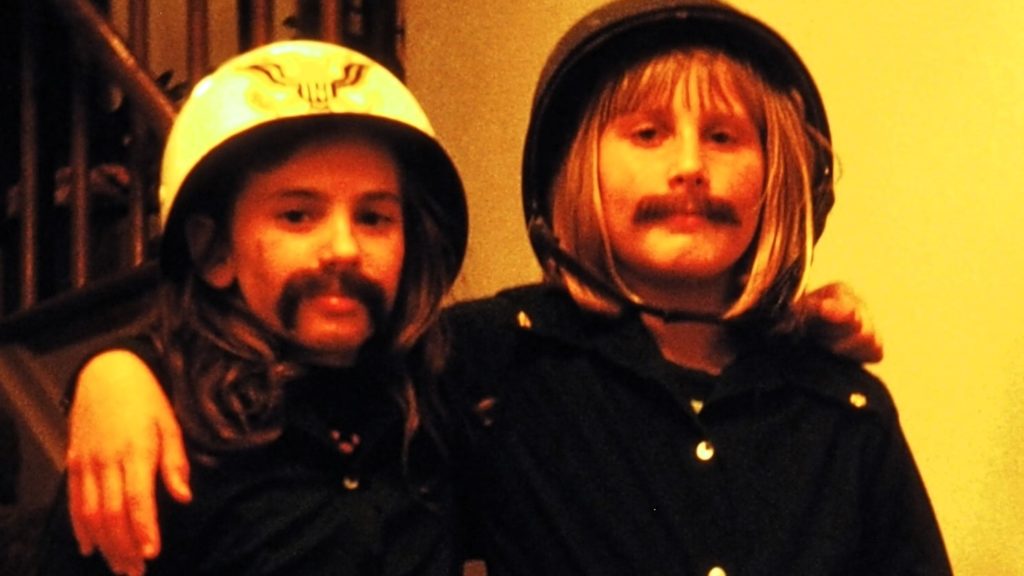

I sometimes wore dresses on holidays and special occasions, but I preferred to wear then-popular polyester leisure pantsuits for girls. Sometimes, I dressed as a soldier or hobo for Halloween. My costumes included a fake mustache because, at the time, only men could be soldiers or hobos. Wearing costumes was ordinary in the life of a kid. It wasn’t seen as a declaration of immutable identity. It wasn’t a medical symptom.

In retrospect, I looked like a junior lesbian, even though I didn’t know what a lesbian was. My best friends were tomboyish girls like me, but all of them developed crushes on boys. I, by contrast, had a big crush on a girl — and I didn’t see any harm in saying so out loud.

From then on, kids at school jeered me and gossiped about my being “a lez.” Their goal was to shame me, I think, but I didn’t feel ashamed. Instead, I was terrified that my feelings — good feelings — elicited inexplicably intense hostility from others.

During basketball practices, I ran laps through school hallways with other kids. Late one afternoon, I turned a corner and a boy named Jim, on the wrestling team, grabbed me and pressed me against a locker. He demanded I prove to him I wasn’t a lez.

I was more angry than afraid because I was straggling behind my team. Jim was slowing me down even more. I pushed him away and kept running.

Still, Jim’s demand haunted me: How could I prove I wasn’t a lez? How many boys did I need to kiss to nullify my crush on a girl? I kissed many boys after that, but had not yet kissed a girl. I proved to myself: Boys were OK, but they had nothing to do with my feelings about girls. A boy was not — and could never be — a substitute for a girl in my affections.

During this time, I could not see stars in the sky. I was increasingly nearsighted but didn’t know it. Eventually, I needed eyeglasses to pass a vision test for my driver’s license.

The first night I wore my new glasses I was startled to see innumerable stars. Had they been there all along? It was like suddenly seeing the face of my guardian angel.

Many years later, I was not a bit surprised to hear that wrestler Jim had grown up to serve a few jail sentences.

Also, my mom ran into Derek, my Suitiful Binderella. He was gay and happy, he told my mom. She was glad to report that I was a lesbian of good cheer.

We were lucky indeed. Had Derek and I been born just a few decades later, Prevailing Wisdom would have told us our bodies were wrong. Our well-meaning third-grade teacher likely would’ve been pushing us toward cross-sex hormones and genital surgeries instead of showing us how to laugh lightly at the absurdities of gender.